How the Security Police blew up four kids

One survived, but died years later. Now a Security Branch explosives expert and an Askari from Vlakplaas are FINALLY on trial – 42 years later. The infamous Askari Joe Mamasela is a state witness.

They were just four young kids from Kagiso township. One was still at school. Enamoured with the romance of the Struggle, they wanted to go into exile and arm themselves to fight apartheid. They paid the price at the hands of a murderous police force and a “friend” who betrayed them.

One of the kids approached a family friend whom he knew was a recently returned MK operative. He asked the operative to help them go into exile. This family friend, unknown to the boy, recently had been “turned” by the Security Police and was now an askari.

This “family friend” betrayed the child and his three friends, and led them into a police trap, where they were blown up by explosives. These four children became known as the Cosas 4.

We know who the cops were. The ones who are still alive today after this terrible betrayal and gruesome multiple murder are still walking our streets – free men.

The reason they are free is because our ANC government for many years refused to prosecute them or their colleagues and superiors. In 1999, when the TRC, which had uncovered the stories and heard many terrible details of apartheid-era atrocities, forwarded evidence of human rights violations and crimes to the National Prosecuting Authority, senior government officials leaned on the NPA and forcibly suppressed the prosecution of all 300-500 TRC cases. Strangely, no-one can actually establish how many cases there were!

It is this second betrayal (by alleged democrats) that families, lawyers, activists and others have fought to right, to ensure these men are found guilty of their crimes and sent to jail.

The Cosas 4, so-named because they were supporters of the Congress of SA Students in the early 1980s, were Eustice “Bimbo” Madikela, Ntshingo Mataboge and Fanyana Nhlapo who were all killed, and Zandisile Musi, who miraculously survived the blast.

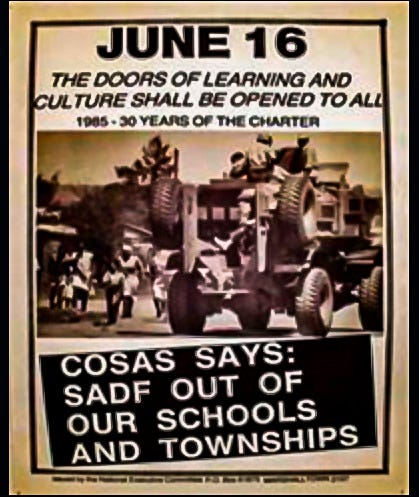

Cosas was an anti-apartheid student organisation established in 1979 following the June 1976 Soweto uprising and the banning of its predecessor, the SA Students Movement (SASM) in 1977. In 1982, with the motto of “Each One, Teach One”, it adopted the theme “student-worker action”, providing essential support to striking workers and community struggles around issues such as transport increases, rent hikes and the like.

In early September 2020, the families of three of the murdered boys filed an application with the Krugersdorp Magistrate's Court for an order to have the bodies exhumed and forensically examined, with a view to a later prosecution of the killers.

But back to the beginning.

After the June 1976 Soweto Uprising, Zandisile Musi was just a small boy when his two elder brothers joined hundreds of others going into exile. A family friend called Thlomedi Ephraim Mfalapitsa, known to the family as “Weston”, also left. Leaving the country was “a serious decision for anybody to make”, Mfalapitsa told the TRC later.

Mfalapitsa was 30 years old when he went to Botswana to join MK. The ANC trained him in Zambia, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, and thence to the GDR, East Germany, via Angola. When he returned to Zambia, he was prepared for deployment to the front area (Botswana). Two of his infiltration missions failed, once when their weapons were discovered by the police.

In 1977/78 he was assigned to infiltrate other guerrillas from Botswana, and by 1979 he was in charge of ordnance (weapons and ammunition) there. He was arrested by the Botswana police and sentenced to three and a half years in jail. Eventually he was discharged and sent back to Zambia, where he was attached to the military HQ of MK, where Joe Modise was the commander. Mfalapitsa was alleged the No 3.

But what he saw in exile upset him greatly. “I participated (in actions) in which people were killed just for indiscipline and grievances, genuine grievances,” he told the TRC. He had to participate in the torture of cadres and the killing of some of them. He realised this was not for him.

Mfalapitsa ran away from the ANC in November 1981.

“Immediately I arrived in SA, I told the SAP that I am not interested in joining either side of the conflict. I wanted them to debrief me and set me free because there was nowhere else to go and this is my country,” Mfalapitsa said.

“And then they refused me. They said they could not let me, after having been in military structures in which Joe Modise is the chief of the armed forces of the MK . . . I was caught in a quagmire of political conflict . . . my political point of view at that stage was actually an evolutionary process . . . I have a very intense distaste for conflict.”

The Security Police debriefed him in Zeerust, and then sent him to Unit C1 based at Vlakplaas, the notorious hit squad farm where turned guerrillas called askaris lived. No-one inside the country knew he had defected, so he was extremely valuable to the police.

Mfalapitsa visited Kagiso township but stayed away from the Musi home because he knew the family would ask him awkward questions about their two sons who had been in exile with him. He claims he met Zandisile Musi in Maulada Street, informally, and Musi asked him to help a group of them leave the country for training.

In February 1982, the dusty township of Kagiso was in the heat of Struggle. The previous December had seen the homeland of Ciskei given “independence”, and the ANC's most successful year inside the country, doubling the number of attacks in any year since 1976, with 55 attacks. MK combatants had used limpet mines, RPG rocket launchers and even attacked the military town of Voortrekkerhoogte with a 122mm rocket launcher. But 21 MK soldiers had been killed during 1981, and the Maputo suburb of Matola had been attacked on 30 January 1981, with three ANC persons abducted by the SA Defence Force. Unionist Neil Aggett had just died in detention (been murdered) that same February.

“And then,” says Mfalapitsa, “I foresaw that something dreadful was supposed to happen.”

He had two thoughts:. The first was that the police had sent Musi to test his loyalty, and if he didn't report the incident, he could be assassinated by the police. The second was that he could leave the country to escape involvement with this incident which would probably lead to the killing of the youths, but then he would have to return to the ANC, and that would be “a dreadful experience”.

He was trapped in a Catch 22 situation. He told Musi they didn't have to leave the country, he could train them locally, and he agreed to meet Musi and his comrades again.

But Musi, who survived the murder attempt, relates it differently: “Tholomedi came to my home . . . late in the evening, about six or seven, to greet our family. We knew that he's been in exile. It was myself and my grandmother and a third person. He came to tell my mother that he was around. And then my grandmother enquired about my other brothers. We used to call him Weston. He said he last saw one of my brothers in Zambia.

“I was with the other comrades in Cosas, who always had the intentions of crossing the border and joining the liberation movement and later become members of ANC.

“We saw him . . . as a person we could trust, and I told him our intentions, but he was in a hurry. He said there was no need to cross borders because the ANC had some structures inside the country.

“He promised to bring us the Freedom Charter and ANC political information. We set another meeting to begin training and (for him) to bring reading material and equipment. A second meeting was held at Industria Station at about 2pm on Saturday 13 February.

“I went back myself to tell the others that we had a meeting at 8 o'clock on Monday at the Leratong Hospital.

Mfalapitsa had reported his initial meeting and that the youths had requested to go into exile. Mfalapitsa's boss at Vlakplaas, Captain Jan Carel Coetzee (not to be confused with Capt Dirk Coetzee who also commanded Vlakplaas at some point), told him to convince them to be trained within the country, so they could then be killed. The murder plot of these children was “cleared” with Coetzee's boss, Brigadier Willem Schoon, who headed the Security Police’s C Unit. Other alternatives, like detention, were not discussed.

A location had been chosen for the training and rigged with explosives by another Security Policeman, explosives expert Warrant Officer Christian Sievert Rorich, whom Coetzee had persuaded to illegally join him for the operation from his normal post at Ermelo.

They went to an old pump house on a deserted mine property near Krugersdorp, where Rorich primed the explosive device and went out to a hiding place in an old building nearby to await the arrival of the activists.

Musi picks up the story: “He (Weston) came with a Kombi with a gentleman with a scar on his face (this was askari Joe Mamasela of Vlakplaas notoriety). We went to a spot that was next to a mine. We walked from the Kombi and we went through the forest to that venue. We were told to rush into that place. We got into a room in the mine. He opened the door. We got inside. He was the first one to get inside and we followed him, the three of us followed him.

“After getting in there, he closed the door. He told us that he was in a hurry. He did not waste time. He took out a grenade in his pocket and a firearm and he put them down. He connected the detonator to the grenade. After that he demonstrated how to pull this detonator. And then he told us that he was coming back. He said he was going to fetch some weapons in the Kombi, which was being looked after by Mamasela.

Mfalapitsa left the pump house, quickly locking the door to trap the boys inside. As he joined the other policemen, Rorich detonated the explosives. They all left immediately.

Musi continues: “After he had left, within a short time, there was a box that I didn't know what was inside that box. When I looked at the box, I heard an explosion.

“We fell. . . . I thought that what had exploded was the object that we had in the hand . . . I couldn't walk, I couldn't see. I tried to cry for help.

“In that process, I was unconscious and I woke up in the (next) morning and I was feeling cold and my clothes were torn. I tried to, tried to shout for help.

“At about eight in the morning, the police came. (Policeman) Mr Nkosi was also there. I could not see, but I tried to open my eyes. Mr Nkosi asked me what is it that I was doing there. . . .

“I was taken to Leratong Hospital. After getting treatment, some stitches and some plaster on my leg, even my face, it was burnt, and they gave me treatment for that. And they (the cops) took me out of the hospital.

“I was taken to a place that looked like a veld. I remember that the car was driving on the grass. A white policeman came out and he put a firearm in my mouth and then he demanded me to tell him who that person was. The one who took us.

“And I told him I did not know the person. And he said I was lying. . . . they took me to Krugersdorp Prison. When I arrived I was put inside a cell. The police would come, even in the evening, they were assaulting me. They demanded the name of this person who gave us the bombs, the explosives. . . . . I think I spent the whole month in there. And I was taken to court. I was granted bail for R500 . . . after that I was acquitted in the court.

After that, Musi spent nearly a year in hospital. He had to have an operation to connect the bones in his one leg, and he had to have an operation to try and fix the explosion damage to both his ears. He could not continue with his schooling. “Everything would flash on my mind just before writing the exam”, he said. He had to lip-read, as his hearing was badly damaged.

During the Amnesty hearings, Coetzee, the commander, revealed that there was never any attempt to investigate the background of the intended victims, nor was any investigation conducted afterwards.

Coetzee shockingly admitted: “I didn't know who they were.” He agreed with counsel that it was “four kids with an idea” and admitted to giving Rorich “not a legal order”.

The families were told the children had “blown themselves up”. The behaviour of the police was extremely callous towards the families, not even telling them where the bodies were.

Maide Selebi said she found out about the murder of her brother (Eustice Madikela) the weekend after it happened. “I was training as a nurse at Tembisa hospital at the time, and I received a call from my mother telling me to come home. She did not tell me why I needed to come home. As I was arriving home on that weekend, I saw that there were a lot of people at my house. Only when I actually arrived at my house did my mother tell me that my brother was dead.”

Her mother had found out from police who came to show her a piece of paper that had her brother's name and address on it (which was her parents' address).

“They asked her if she knew this person. When she replied yes, they told her that he and two others had blown themselves up and that this piece of paper had been found at the warehouse where they blew themselves up.”

“My mother was asked to identify his body at the morgue, which she did. She said his body was badly blown up. “ Her mother died in July 1986, just three years later.

The three were buried hastily without the mandatory post mortem to prevent the police removing the bodies to undisclosed sites. There was no inquest, as legally required. The security police covered up the murders.

No-one ever would have known until Mfalapitsa, racked with guilt and now a pastor, applied to the TRC for amnesty, thereby forcing his police companions to do the same.

Now that the families have applied for the exhumation of the bodies, the NPA claims the legal request is “premature”. The callousness of the NPA lawyers is just amazing: 38 years later, 21 years after the TRC, and getting to the truth is “premature”?

The NPA has a duty to perform. It's taken time, but finally these murderers have been brought to trial. Whether justice will ever be served is another question.*

Former SAP SB member Thlomedi Ephraim Mfalapitsa told the TRC about the deaths in a hearing held on 4 May 1999 during the Amnesty Application of Jan Carel Coetzee, Willem Frederick Schoon, Abraham Grobbelaar, Christian Sievert Rorich and Mfalapitsa. Case # AM3592/96. Coetzee, Schoon and Grobbelaar have all died before they could be brought to justice.

Updates to the trial will be posted here periodically.

David Forbes is a documentary filmmaker, writer, artist activist, tour guide and social commentator who made the award-winning film The Cradock Four in 2010.